Pitvipers in Peril

Published:

Despite their fearsome reputation, numerous rattlesnake species are in decline throughout the United States. Why should we care?

The Ecological and Cultural Case for Rattlesnake Conservation

Rattlesnakes play vital roles in the ecosystems they inhabit, helping to control rodent populations and limiting the spread of rodent- and tick-borne illnesses. Despite their fearsome reputation, rattlesnakes are far from the mindless predators they are often made out to be. They are secretive, generally docile, and reluctant to strike. In fact, research has shown that rattlesnakes recognize their relatives, form social groups, and guard their young (Tetzlaff et al., 2023; Clark, 2004; Green et al., 2002). Yet persecution of rattlesnakes in the United States has persisted for centuries, leaving lasting scars on their populations. One such species is the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), which has endured relentless threats, from habitat loss and disease to human fear and folklore.

An Icon in Decline

The timber rattlesnake is a large-bodied pitviper native to the woodlands of eastern North America. Historically, it ranged across 35 U.S. states and likely reached into Ontario and southwestern Quebec (Curran & Kauffeld, 1937; Martin et al., 2008). Though still present in 31 states, the species now exists in fragmented and increasingly isolated populations, threatened not only by habitat loss but also by human persecution, climate change, and infectious disease (Martin et al., 2008).

Once celebrated as a symbol of courage and independence during the American Revolution, the timber rattlesnake appeared on the Gadsden flag above the words “Don’t Tread on Me”, and earlier, on Benjamin Franklin’s famous “Join, or Die” illustration of a severed snake representing the disunited colonies. Even as rattlesnakes were adopted as patriotic icons, living populations were already in decline.

Eradication efforts targeting the timber rattlesnake date back to the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly in the northern states where communal dens made the snakes easy targets (Brown, 2021). Bounties paid for dead rattlesnakes continued into the late 20th century, with rewards ranging from 25 cents to five dollars (Brown 1993; Brown 2021). These programs had a devastating impact on survival and distribution in states such as New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Pennsylvania (Brown, 2021; Martin et al., 2008). Thousands of snakes were killed, and entire local lineages likely vanished.

This loss is particularly devastating given the species’ slow life history. Female timber rattlesnakes take nearly a decade to reach reproductive maturity, and many reproduce only once in their lifetime (Brown, 2016). In their northern range, timber rattlesnakes display ‘communal hyperfidelity’, wherein individual snakes often return to their natal den sites year after year (Brown 2016; Tetzlaff et al. 2023). During the active season, large numbers of snakes congregate at birthing rookeries, where pregnant females gather to bask while gestating and provide parental care to newborn litters (Tetzlaff et al. 2023). While these behaviors may offer benefits like enhanced vigilance and kin-based defense (Clark, 2004), communal hyperfidelity can also be maladaptive in an era so impacted by environmental change (Tetzlaff et al., 2023). Tethered to specific shelters, these snakes may struggle to disperse when local conditions deteriorate, limiting gene flow and increasing isolation (Tetzlaff et al., 2023). Furthermore, this fidelity has historically made them easy targets. Entire denning communities were wiped out during colonial and post-colonial eradication campaigns, likely destroying entire family lineages of snakes. Rattlesnakes have long been viewed as solitary and unsociable, unfeeling and even malicious. Were this actually true, timber rattlesnakes might have proven more difficult to drive to the brink of extinction in certain regions. Today, populations are struggling to recover from the demographic bottlenecks inflicted by centuries of persecution and illegal poaching.

Today, the species’ most intact populations remain in the heavily forested Coastal Plain and mountainous interior of the eastern U.S., but habitat fragmentation is severe in the Midwest, Piedmont, and at the edges of the species’ range (Martin et al., 2008). As development continues, road mortality and population isolation compound these risks. Climate change and the emergence of fungal diseases further jeopardize long-term survival (Clark et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2011).

A Co-evolving History of Rattlesnake-Human Interactions

Formally described in 1758 by Carolus Linnaeus in Systemae Naturae, the timber rattlesnake is the first rattlesnake species to be described from the Americas. The species bears the scientific name “horridus”, meaning ‘dreadful, horrible, or bristly, likely referring to the snakes’ venomous bite or the rough appearance of its keeled scales.

Long before European naturalists assigned it a name, the timber rattlesnake roamed North America for hundreds of thousands of years. Fossil records date back 0.5 to 1 million years (Martin et al. 2008; Holman, 1995), and Indigenous peoples of eastern North America have shared the landscape with these snakes for thousands of years. The Mdewakanton Sioux called them sin-tah-da, meaning “yellow rattlesnake” (Keyler, 2023; Schoerger, 1968). The names we give species often reflect how we perceive them, shaped by cultural perspectives and biases. It is fascinating to think of what other names these snakes were given during the thousands of years before colonization.

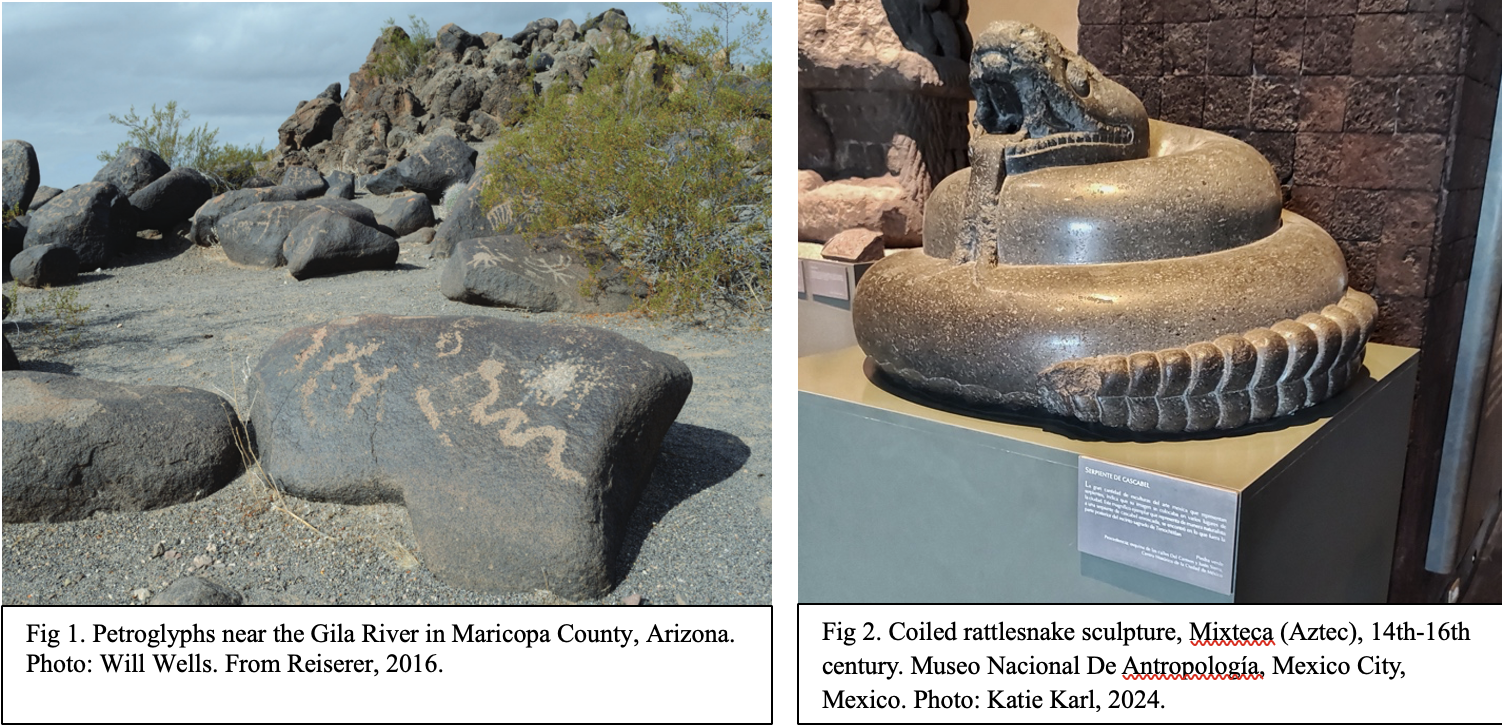

Rattlesnakes have long held a place in the cultural traditions of Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. The first humans to reach rattlesnake territory likely arrived over 14,000 years ago (Reiserer, 2016; Gilbert, 2008). Initial encounters with an unfamiliar and formidable animal were probably harrowing, marked with fear, injury, and heartbreak. Yet, over time, generations of lived experience and accumulated knowledge gave rise to diverse cultural traditions. Across the Americas, rattlesnakes became woven into stories, ceremonies, and belief systems, many of which recognize these creatures as something to respected and honored.

The Hopi of the U.S. Southwest included rattlesnakes in biennial rituals, entrusting the snakes with prayers and releasing them as messengers to the spirits responsible for bringing rain (Murphy & Cardwell, 2021; Reiserer, 2016). In many Native cosmologies, the snakes’ subterranean habits associated them with the underworld, linking them to themes of transformation and the afterlife (Robles, 2021).

Choctaw storyteller Tim Tingle recounts how the Lower World within Cherokee cosmology is inhabited by snakes and other subterranean dwellers. Snakes (ndädû in the Cherokee language) hold great power, and killing one snake is considered a grave and fatal offense by all snakes (Tingle, 2006). A 19th-century account from a Cherokee man named Blanket, recorded by a missionary, describes how some western Cherokee avoided harming rattlesnakes out of mutual respect for the snakes’ strong family ties (Robles, 2021; Washburn, 1869).

At Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) constructed a sophisticated system of solar and lunar observatories, including shadow markers used to track the solstices and equinoxes (Reiserer, 2016; Sofaer et al., 1982). Among these petroglyph markers are depictions of rattlesnakes, evidence that these animals were not only spiritually significant but also served as symbolic markers of cyclical time and natural order in the southwestern landscape.

Rattlesnake Roundups: A Legacy of Fear

Today, one of the greatest challenges to rattlesnake conservation is shifting public perception. The legacy of early extermination campaigns still lives on through practices like modern-day rattlesnake roundups.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Sweetwater, Texas, where an annual roundup has occurred since 1958. Here, hundreds, sometimes thousands, of western diamondback rattlesnakes are captured, decapitated, and displayed for sport. For a small fee, attendees can skin snakes themselves and place their bloody handprints on a wall. The rationale is public safety, yet western diamondbacks kill approximately one person per year in Texas, and the only fatality in 2022 was a handler at a roundup (Williams, 2024).

Rattlesnakes are often flushed from their burrows using gasoline. Still legal in Texas, this method destroys delicate burrow ecosystems and is lethal to the animals inside. More than 360 native species depend on these burrows for food and shelter (Center for Biological Diversity, 2024).

Some communities, however, have rejected these inhumane traditions. In Georgia, the Claxton Rattlesnake & Wildlife Festival transitioned into a non-violent celebration of biodiversity. Today, it partners with herpetologists, environmental organizations, and state agencies, and has proven more profitable and better attended than the roundups it replaced (Williams, 2024).

Why Rattlesnakes Matter

So, why should we care about rattlesnakes?

There are plenty of practical answers. They help control rodents. They reduce the spread of disease. They are prey for other species. They even assist in seed dispersal (Schuett et al. 2022).

But perhaps the most powerful reason is this: rattlesnakes are sentient animals with complex lives, deserving of respect. They can live for decades. They care for one another. They feel pain.

The future of rattlesnake conservation depends not only on sound science, but on public empathy. And we cannot have one without the other. Research on rattlesnakes remains chronically underfunded, a reflection of lingering public hostility toward these misunderstood creatures. Rattlesnakes need both our curiosity and protection to survive. In order to preserve these iconic species for generations to come, we must shift the narrative from one of fear to one of fascination.