Endlings and Beginnings

Published:

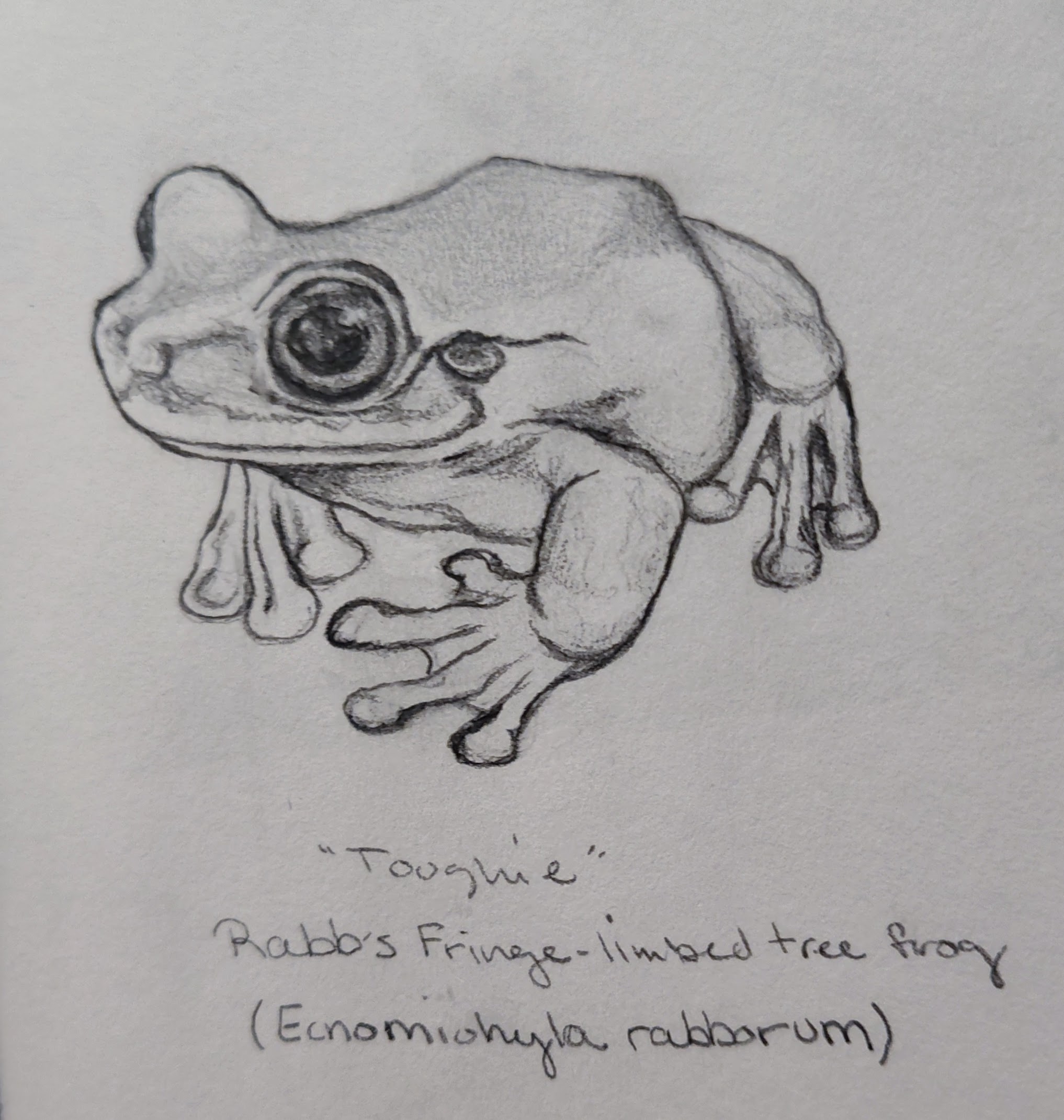

On this day in 2016, the world quietly lost a species. “Toughie,” the last known Rabb’s Fringe-limbed Leaf Frog (Ecnomiohyla rabborum), passed away in captivity, marking the extinction of his kind.

Toughie was an endling- the last known survivor of his species. Toughie was collected by a team of biologists in 2008 during a mission to rescue Panamanian amphibians from Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a deadly fungal pathogen responsible for the global amphibian crisis. He was one of several of his kind brought back to the United States with the hope of establishing assurance colonies - captive populations created to prevent complete extinction [1]. Unfortunately, attempts to establish a captive breeding population were unsuccessful; while eggs were laid, the tadpoles proved exceptionally difficult to raise. One by one, the adult frogs grew older and began to succumb to age.

Toughie was given his name by the young son of his long-term caretaker, Mark Mandica. Mandica cared for Toughie for nearly 8 years at the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

When Toughie was transported to the United States, his species did not yet have a formal scientific name. In the formal description of Ecnomiohyla rabborum, biologists described the species as “spectacular” [2]. This word is truly fitting.

Rabb’s Fringe-limbed Leaf Frogs were striking in both form and behavior. Their massive, webbed feet allowed them to glide between trees in the dense forest canopy. Their skin, mottled brown with flecks of green, was capable of metachrosis; the ability to change color at will. In the wild, these frogs lived in hollow tree holes, where they raised their tadpoles in the rainwater that pooled inside. Male frogs were observed spending their days half-submerged in the water, while tadpoles swam around their bodies, feeding on small flecks of skin. This is thought to be the first example of direct paternal nutrition of offspring in an amphibian [2,4].

The last known observation of E. rabborum in the wild occurred in 2007: a single male was heard calling, though never seen [2].Deforestation had long threatened Panama’s rich frog diversity, but until 2005, the immediate area where Toughie’s species lived had remained relatively intact. That changed with the arrival of chytridiomycosis, a deadly disease caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis or ‘Bd’. Bd swept through the cloud forests, devastating amphibian populations [2,3]. Treetops that once echoed with the chorus of gliding frogs and other canopy dwellers fell silent.

In Atlanta, Toughie was silent too. He hadn’t made a sound since shortly after his arrival in Georgia in 2005. On December 15, 2014, Toughie called once again, his first and last vocalization in years. Likely an advertisement call for a mate, it went unanswered. He was already the last of his kind. Listen to his call here.

Toughie’s story is undeniably tragic. The loss of his species leaves an irreplaceable void in the forest community from which it came. Dr. Joseph Mendelson, one of the biologists who formally described Toughie’s species, refers to this phenomenon as “Forensic Taxonomy”, the act of formally describing species just as they go extinct, or after they’re already gone [4].

Toughie not only served as the final ambassador for his species, but as a representative for the numerous amphibian species still fighting in the race against extinction. Amphibians around the world continue to face immense challenges, from emerging diseases to climate change. However, Toughie’s legacy does not have to be one of only despair.

Thanks to the tireless work of conservationists, biologists, and community advocates, many of whom were inspired by stories like Toughie’s, there is still hope. New data concerning the natural history and vocalizations of fringe-limbed frogs is being published [5,6], new strategies to mitigate chytrid are under development [7], and crucial habitats are being protected through local and global efforts.

Members of the team that described and diligently cared for Toughie are still working to conserve endangered amphibians around the world. After the closure of the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s amphibian center, Mark Mandica went on to found the Amphibian Foundation, an organization dedicated to saving as many threatened species as possible. You can learn more about the Foundation’s work here:

Toughie’s DNA will endure as well. Samples of his genetic material have been stored at the Frozen Zoo, a biorepository maintained by the San Diego Zoo’s Beckman Center for Conservation Research [8]. While de-extinction is not a viable avenue for resurrecting this species, Toughie’s genetic code may still provide valuable insight into the evolutionary history of these incredible gliding frogs.

It is too late to save Toughie’s species, but we can honor his life by helping those species still clinging to survival. His quiet call in a garden far from home, once the solitary voice of a vanishing species, now serves as a call to action and a reminder of what can still be saved.